This is a story about love, care, and traveling with grace — even when the journey is hard.

Travel teaches you many things.

Patience. Flexibility. How to pack shoes for every possible climate.

And if you travel with a parent in a wheelchair, it teaches you exactly which cities were designed centuries before anyone considered ramps.

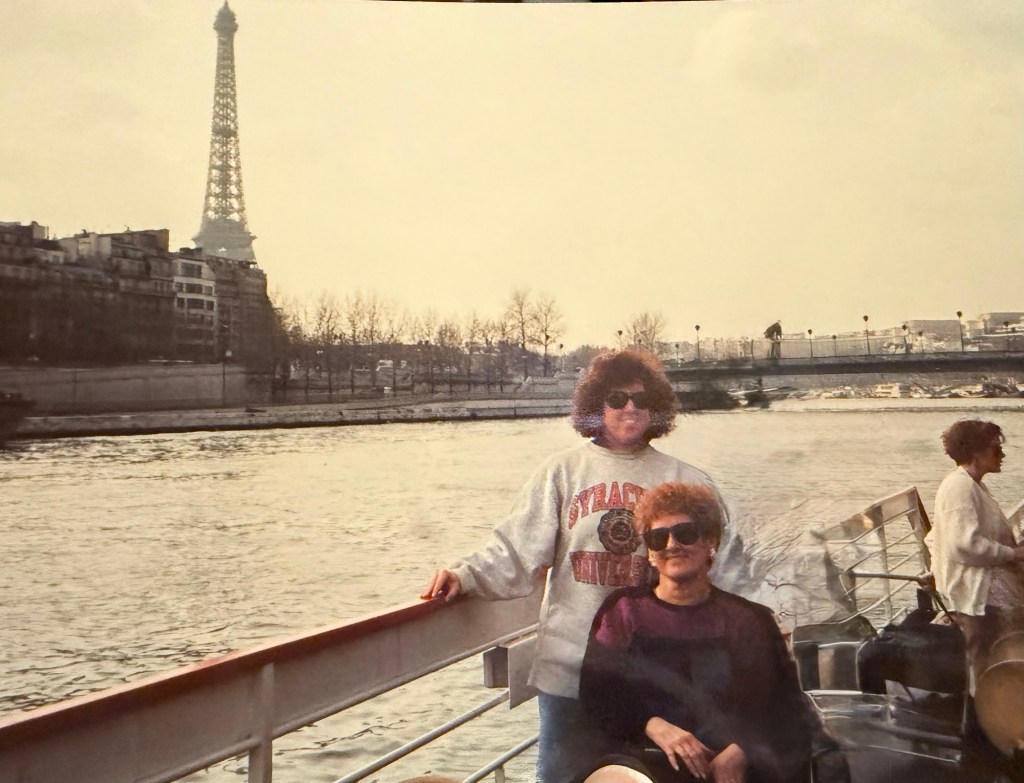

My mom went into a wheelchair at just 38 years old and lived the next 30 years as a paraplegic. She died at 68. We traveled when we could—London, Paris, museums, cafés—but there was so much of the world she never got to see.

Paris, in particular, will always have my heart—and my upper body strength. I bounced my mother’s wheelchair over cobblestones at Versailles that were apparently installed during the reign of Louis XIV and have never been questioned since. Each jolt felt like a reminder that charm and accessibility are not always on speaking terms.

London wasn’t much better. Elevators were elusive, ramps were mythical, and I became fluent in the phrase, “Is there any other way in?” Sometimes the answer was yes. Sometimes the answer was a polite British version of “absolutely not.”

And then there’s Dubrovnik.

Dubrovnik is stunning. Breathtaking. A medieval masterpiece. It is also a place where I genuinely do not understand how anyone with mobility challenges lives—or even survives—on a daily basis. Narrow stone streets. Steps everywhere. No curb cuts. No ramps. No Americans with Disabilities Act riding in to save the day.

Every time I see photos of Dubrovnik now, all I can think is:

“Well, it’s beautiful… but my mom would still be at the city gate.”

But the real adventure often began before we ever reached a cobblestone.

Air travel with a paraplegic parent is not for the faint of heart. Once my mom was seated on the plane, that was it. No getting up. No squeezing past strangers to reach the bathroom. The aisle might as well have been the English Channel.

So when nature called at 35,000 feet, improvisation became our in-flight entertainment.

Her caregiver and I would create what can only be described as a makeshift privacy suite—a carefully draped blanket, strategic positioning, and whatever supplies we had on hand—so we could empty her catheter with privacy and dignity. We weren’t trying to be sneaky. We were trying to be humane.

There is nothing glamorous about managing medical care in an airplane seat, but there is something deeply humbling and intimate about caring for someone you love in the most unromantic circumstances imaginable.

Flight attendants were kind. Passengers were mostly oblivious. And my mom—ever the realist—handled it with grace and humor. If there was embarrassment, it never belonged to her. It belonged to the situation.

Traveling with my mom gave me a front-row seat to a reality many people never notice. When you’re able-bodied, you glide through cities without thinking about curbs, stairs, aisle widths, or bathrooms. When you’re pushing a wheelchair, the entire world becomes a very detailed obstacle course.

Those trips taught me resilience, creativity, empathy—and a deep appreciation for strong arms and stronger women. They also taught me that accessibility is not universal, progress is uneven, and “historic preservation” often seems to mean “we’re keeping it exactly as inconvenient as it was in 1450.”

After my mom died, something shifted.

Now I feel like I travel for both of us.

Everywhere I go, I pick up a small stone. Nothing special. Just something from that place. When I come home, I take it to the cemetery, place it on her headstone, and tell her about my travels—where I went, what I saw, what made me laugh, what made me think of her.

I like to imagine she’s finally seeing the world the way she always wanted to.

Paris gave me romance.

London gave me patience.

Dubrovnik gave me perspective.

And my mom gave me a lifelong understanding that dignity travels with you—even when the world makes it harder than it should

From Juju with live 💙✈️

Champs-Élysées

Leave a comment